The sculptures of Mister Finch, a British textile artist, conjure up a mesmerizing world of sleepy dormice and March hares, magical mushrooms and mischievous fairies, of Victorians romancing fantasy and nature. One of the works in particular (pictured here) caught my eye. The mouse is titled Felinka, but unlike the mice of Fairy- and Wonderland, Mister Finch’s mouse happens to be gigantic—at least for a mouse. Rivaling the capybara, the planet’s largest rodent, Felinka measures more than three-feet across and has a tail that’s five feet long.

Often referred to under the umbrella of the cuddly-sounding art form “soft sculpture,” each of the works Finch creates are sewn from remnants of new and vintage cloths, recycled clothing and table linens. The pieces are as meticulously realistic as they are fanciful; they’re as hard as they are soft.

While articles about Finch’s work almost invariably point to the Pop artist Claes Oldenburg, considered ‘the creator of soft sculpture’ with his three-dimensional interpretations of everyday objects, the use of non-traditional, malleable materials—felt, foam and fabric and animal skins sewn and stuffed for example—can be traced back to the first half of the twentieth century and the works of the Surrealists, including Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Meret Oppenheim. That being said, perusing his website and the press, I get a sense that Finch (the Mister he added to reference his gender, meaningful in that he is a man who sews) is hardly the sort who is preoccupied with his place on art history’s spectrum. He seems to prefer to spend his days in his studio working late into the night, sewing his sculptures to the steady patter of the Yorkshire rain.[1]

He completed Felinka in April of 2013. In an email, he wrote, “I’m drawn to creatures with eyes closed as it has more room for interpretation,” and added, “a huge mouse was something I always wanted to make…”[2]

“Do we need [enchantment] now more than ever?” a journalist recently asked him what feels to me today like an urgent question. To which Finch replied, “I don’t believe it ever went away.”[3]

.

[1] Laren Stover, “Faeryland and Toadstools Arrive in Chelsea, Courtesy of Mister Finch,” The New York Observer, June 10, 2015.

[2] Email to author, December 28, 2015.

[3] Stover, “Faeryland and Toadstools Arrive in Chelsea, Courtesy of Mister Finch.”

Additional sources: Steven Kasher Gallery, NYC; “Viewfinder,” T Magazine, The New York Times, December 3, 2015.

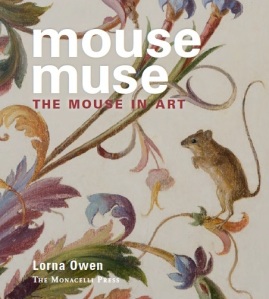

(Image: Felinka Mouse, 2013, unique hand-sewn sculpture made from a mixture of fabric, paper, wire and plastic details.)