Severely myopic young Theodore Roosevelt professed a passion for all sorts of wildlife. But until the age of fourteen, when his father bought him a pair of glasses, his most keen observations of nature were limited to the wild animals he could see close up, the ones he toted home: a family of young gray squirrels he fed milk via a syringe; a disagreeable woodchuck he tried to tame; and “a gentle, pretty, trustful white-footed mouse which reared her family in an empty flowerpot.”[1]

Severely myopic young Theodore Roosevelt professed a passion for all sorts of wildlife. But until the age of fourteen, when his father bought him a pair of glasses, his most keen observations of nature were limited to the wild animals he could see close up, the ones he toted home: a family of young gray squirrels he fed milk via a syringe; a disagreeable woodchuck he tried to tame; and “a gentle, pretty, trustful white-footed mouse which reared her family in an empty flowerpot.”[1]

Explorations in natural history through books came a whole a lot easier for Roosevelt than any of his hands-on efforts out in the field. His heroes were Darwin, Huxley and Audubon. When he was ten years old he set up his own small natural history museum on the second floor of his family’s house in New York City, where he tagged the animals he had learned to stuff from his father. Later he donated twelve taxidermic mice to the American Museum of Natural History before its grand opening in 1877.[2]

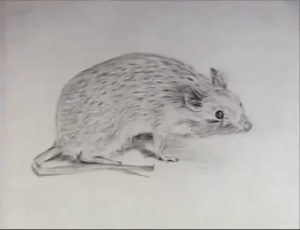

But it wasn’t all about dead animals for the boy who would one day become the 26th President of the United States and celebrated for championing the protection of America’s wilderness. In addition to the mouse that lived in the flowerpot, other live mice served as his models for the drawings he carefully made, depicting each white-footed species. And when he went off to Harvard, his apartment off campus was said to be filled with litters of mice—whether he had brought them with him or whether his college residence was already infested, we’ll never know. Roosevelt never seemed to lose his love for “beasts and birds,” as he referred to them (no invertebrates, please!). Once he was nestled in the White House, now with children of his own, among the colorful collection of family pets—a badger, a pig, an iguana and a bear cub all of which roamed freely around the White House’s corridors and grounds—was Nibble the mouse.[3]

.

[1] Theodore Roosevelt, “My Life as a Naturalist,” American Museum Journal, May 1918.

[2] Quoted by Douglas Brinkley in The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America, from David McCullough’s Mornings on Horseback.

[3] “American Experience: TR, The Story of Theodore Roosevelt,” PBS.

(Image: Juvenile drawing of a mouse by Theodore Roosevelt, Houghton Library, Harvard University.)

Leave a comment