Like her fellow Netherlander Hieronymus Bosch who put a mouse in a glass container in his painting the Garden of Earthly Delights five hundred years earlier, Liselot van der Heijden put two mice in a white box with a glass front for her video piece. The artist’s installation is as spare as Bosch’s triptych is teeming. Nevertheless both works stir the same pot—in a manner of speaking: First Sin. While one is biblical, Adam and Eve out of control, the other is political, the United States’ leader run amok.

Like her fellow Netherlander Hieronymus Bosch who put a mouse in a glass container in his painting the Garden of Earthly Delights five hundred years earlier, Liselot van der Heijden put two mice in a white box with a glass front for her video piece. The artist’s installation is as spare as Bosch’s triptych is teeming. Nevertheless both works stir the same pot—in a manner of speaking: First Sin. While one is biblical, Adam and Eve out of control, the other is political, the United States’ leader run amok.

The New York City-based photographer and video artist van der Heijden created See Evil, Hear Evil, Speak Evil in 2006, against the backdrop of the agenda the Bush administration was pursuing; “a parody,” we’re told, “of the deceptive and manipulative use of Good and Evil to frame foreign and domestic policy… when evil is thought of as not-human, as a thing, or a force, something that has a real existence…”[1] Language and symbolic power are recurring themes in her work.

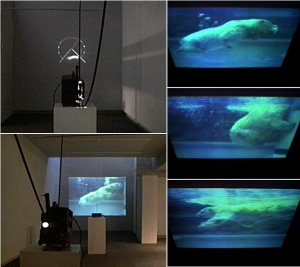

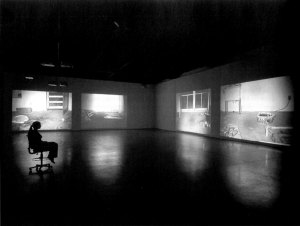

Three wall-size screens are positioned inside a rectangular space. On the screen at the end, opposite the opening, is a video of a single snake coiling and uncoiling, slithering slowly inside a white box similar to that of the mice, on a twenty-five minute loop. The snake segment is called Serpent—that trickster-tempter of divine knowledge. And on an adjacent small television screen is George W. Bush using the word “evil” in far too many ways, culled from his State of the Union speeches. “Evil is real”; “to see the true evil”; “to hear claims of evil”; “to speak with evil,” the 43rd President says. Meanwhile the mice are displayed to the left; their footage is called Trap. In a continuous replay of twenty minutes, the tiny creatures run around looking for a way out, distracted intermittently by a red apple, the proverbial forbidden fruit. On the facing wall to the mice is a reflection of the mice video and the viewers themselves, courtesy of a real-time feed from a surveillance camera. According to the artist, “representations of nature reveal more about cultural, ideological, political and social frameworks, than actual nature.”[2] We and the mice are one. Bosch, I think, would approve.

.

[2] Ibid.

Additional sources: LMAK Projects, “See Evil, Hear Evil, Speak Evil: Liselot van der Liselot van der Heijden,” The Village Voice, October 27th, 2006.

(Image: Trap, video still, copyright Liselot van der Heijden.)