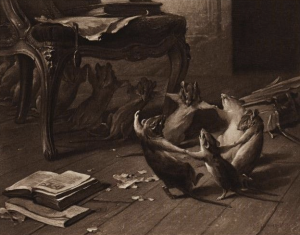

Some one hundred years ago “waltzing” mice were a sought-after pet, a novelty bred solely for their quickstep ability. Despite what this print of mice might charm us into believing, the real-live diminutive creatures danced on all four legs, never on two. Sometimes they spun around an invisible vertical axis or in a figure eight as they twitched their heads about. Sometimes two mice danced together in a synchronized fashion. And sometimes two mice danced like a planet orbited by its moon—while one spun in a wide circle, the other circled the spinner.

Some one hundred years ago “waltzing” mice were a sought-after pet, a novelty bred solely for their quickstep ability. Despite what this print of mice might charm us into believing, the real-live diminutive creatures danced on all four legs, never on two. Sometimes they spun around an invisible vertical axis or in a figure eight as they twitched their heads about. Sometimes two mice danced together in a synchronized fashion. And sometimes two mice danced like a planet orbited by its moon—while one spun in a wide circle, the other circled the spinner.

Along with their kin fancy mice—varieties of house mice who earned the fancy in their name having been selectively bred and prized for their exceptional coat colors, such as blue and yellow and albino—the waltzing, commonly piebald, mice were domesticated in 18th century Japan. Scientists speculated that they resulted from a natural mutation that occurred centuries earlier in a mouse who was once indigenous to the plateaus and plains of Central Asia—a tiny dancer was mentioned as early as 80 B.C. in the annals of the Han Dynasty. China by way of Japan, the now-called Japanese waltzers arrived in Europe with the help of European traders throughout the nineteenth century, and by the late 1890s these nimble-footed individuals began to appear in the United States.[1]

From 1903 to 1907, Robert Yerkes, a behavioral psychologist and a professor at Harvard University observed from two to one hundred “graceful and dexterous” little dancers and published the results in an aptly titled book The Dancing Mouse.[2] In addition to his probe into their development and their physiology, looking for deviations from ordinary mouse species, he broke down their dance steps, whirling to the left or whirling to the right or whirling back and forth to the left and right. The left whirlers, who were mainly female, outnumbered the right whirlers, who were mainly male. Both sexes, however, whirled more and more as day turned to dusk.

The Japanese waltzing mice, as it turned out, were not dancing because they heard songs in their heads. In fact when they were born they hardly heard anything at all, and by the time the mice were one-week old the majority of the dancers were completely deaf. Most scientists concurred that both the deafness and the unusual behavior were probably due to a hereditary structural abnormality of the inner ear. While they disagreed as to the precise location—the ear canals or the cochleae or the ligaments of the cochlear ducts—and pointed fingers at one another, claiming carelessness in their methods, they agreed that the mice’s twirling was nothing but their lifelong quest to stay upright.[3] Alas.

The tiny waltzers no longer exist. Perhaps because almost the second after the mice had reached our shores, scientists nabbed them and crossbred them, over and over, with a number of other strains. One thing that can be said, any dancing mice are better left to the imagination of artists.

This print is by the 19th century French artist Charles Hermann-Léon, highly esteemed for his paintings of animals. Published in 1891 its caption reads: Quand les chats n’y sont pas…,[4] taken from the well-known French proverb, “When the cats aren’t there…” (or the English version “When the cat’s away…”) We all know what comes next: The mice will dance!

.

[1] William H. Gates, “The Japanese Waltzing Mouse, Its Origin and Genetics,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Volume 11, 1925.

[2]Robert M. Yerkes, The Dancing Mouse: A Study in Animal Behavior, 1907.

[3] In the 1930s, a leading mammalogist Lee Dice of the University of Michigan discovered the same dancing behavior and ear defects in four strains of deer mice, Lee R. Dice, “Inheritance of Waltzing and of Epilepsy in Mice of the Genus Peromyscus,” Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Feb., 1935)

[4]The source of the print is unknown.

(Image: “Quand les chats n’y sont pas…” by Charles Hermann-Léon, photogravure print, 6 ¼ x 4 7/8 in., published 1891.)